Metallica has always had a love-hate relationship with its fans. Beginning with its controversial decision to film a music video for the first time for the anti-war song “One” and continuing with the shift from heavy metal thrash to more “commercial” rock songs on the Black Album, Metallica has routinely challenged the expectations of the public.

More famously, on April 13, 2000, Metallica inflamed the good nature of its fan base by suing Napster in federal court for copyright infringement, racketeering, and unlawful uses of digital devices, among other causes of action.[1] As part of this lawsuit, Metallica identified over 300,000 individual users who allegedly copied and unlawfully acquired digital copies of Metallica’s songs through the Napster peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing service. These users were “temporarily” banned as a result of Metallica’s investigation and lawsuit.[2] Not surprisingly, Metallica faced a severe public backlash for attacking its purported fans through lawsuits and allegations of copyright infringement. It even inspired a classic South Park episode.

Metallica is accordingly well-known to be litigious. They will strongly enforce trademark rights and all of their copyrights, when necessary. This often does not sit well with music fans that view the band as entitled and out-of touch millionaires. This leads to the most recent unfavorable public relations snafu by Metallica.

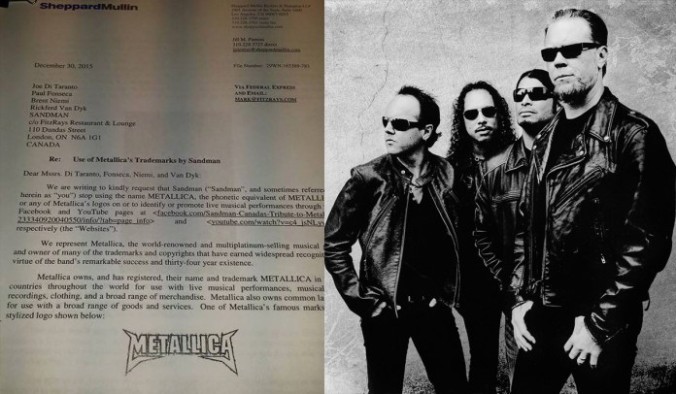

On December 30, 2015, Metallica’s lawyers sent a cease-and-desist letter to a Canadian tribute band performing under the name “Sandman.” Why did Metallica go after a tribute band? How is this different from the Napster case?

The law firm of Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton LLP[3] represents Metallica on issues of intellectual property matters. Apparently, a Canadian band named “Sandman” is a tribute band that performs covers of Metallica songs, and even took its name from one of Metallica’s biggest hits, “Enter Sandman.” Unfortunately, to market itself the band was allegedly using a logo that was confusingly similar to Metallica’s famous stylized logo and name, which is protected by a multitude of federally registered trademarks.[4] The band also used the name “Metallica” as part of its advertising for live music performances. The band expressed shock and surprise when it received the cease-and-desist letter which demanded that the band cease using the “official, stylized logos”[5] in live performances and through Facebook and YouTube. Almost immediately, the band shared the news on Facebook with a copy of the letter.

The online backlash was swift and severe.

Unlike the Napster matter, the band immediately reversed course and claimed that the letter was the product of an “overzealous attorney” and that it is a misunderstanding. The band claimed no knowledge of the letter prior to being made aware of the events on social media. Lars Ulrich, the drummer and founding member of Metallica, also purportedly gave Sandman his “full blessing” to continue as they were and that the cease-and-desist letter has been rescinded. I guess Metallica learned its lesson from its prior PR nightmares? Or maybe Lars finally made enough money to buy his own shark tank and does not care anymore?

But … were the lawyers wrong to send the letter?

There are substantial distinctions between Metallica’s decision to sue Napster for copyright infringement as compared to any decision to potentially enforce its trademark rights in the Metallica name and logo. Copyright law does not require the owner or author of a copyright to enforce its rights against all potential infringers. Copyright is not lost or abandoned if an infringement is not stopped.[6] Metallica does not have any affirmative duty to enforce any of its copyrights, even if they are registered. Metallica’s decision to go after Napster was a conscious decision by the band to protect its copyrights, but it was not a legal requirement. Nevertheless, the passage of time has potentially demonstrated that Metallica was ahead of its time in trying to stop the unfettered file sharing of its substantial catalog of music. Was Lars right?

In contrast, Metallica has a legal duty to police the market against any unauthorized uses of its trademarks.[7] Metallica admittedly was unaware of Sandman’s use of the Metallica name and the modified logo. This is why Metallica hires outside counsel – for the purpose of policing the market for such unlicensed uses and sending cease-and-desist letters. While Metallica later rescinded the demand and granted Sandman their blessing to use the logo and Metallica’s name in a descriptive sense, this does not change the fact that Sandman was technically using Metallica’s trademarks without permission and should not have been surprised to be threatened with legal action.

Worth noting, however, is that any claim that Sandman was using the METALLICA name unlawfully might reasonably be subject to the defense of “descriptive fair use” of trademarks. To the extent Sandman used Metallica’s name only in the nominative sense to describe that it was a “tribute” band inspired by Metallica and its music, this should be considered fair use and not an unlawful use. Nominative fair use “permits use of another’s trademark to refer to the trademark owner’s actual goods and services associated with the mark.”[8]

In the end, Sandman now has an actual or implied license to use Metallica’s name and logo anywhere it roams. But Metallica was legally in the right to enforce its trademarks. Sad but true.

[1] http://news.findlaw.com/hdocs/docs/napster/napster-md030601ord.pdf

[2] Most just changed usernames and re-joined Napster thereafter.

[3] http://www.sheppardmullin.com

[4] See U.S. Trademark Reg. No. 20/38,081 (February 18, 1997), among a series of other METALLICA marks.

[5] It appears that Sandman’s logo was a modification of Metallica’s logo from the “St. Anger” album cover.

[6] https://www.plagiarismtoday.com/stopping-internet-plagiarism/your-copyrights-online/3-copyright-myths/

[7] This duty is not statutory or part of the Lanham Act, but common law and case law precedent sets forth the obligation to protect trademark rights by policing the marketplace. See generally, 2 J. Thomas McCarthy, MCCARTHY ON TRADEMARKS AND UNFAIR COMPETITION § 11:91 see also 1 McCarthy § 2:15 (“A trademark is a kind of property, but a very delicate property right it is. Great care must be taken in the nature of its use, and in the manner in which it is assigned or licensed, lest the significance of the mark be lost.”).

[8] http://www.inta.org/TrademarkBasics/FactSheets/Pages/FairUse.aspx.

Recent Comments