[originally published September 25, 2015 on www.law-dlc.com]

Have you ever watched a movie and wondered whether something cool in it could be patented? Many movies, however, are set outside the United States. Some are set in fantasy lands that would not recognize our system of laws. Yet – what if? What if, for example, the mythical country of Florin happened to adopt the laws of the United States as it applies to intellectual property rights? Yes, Florin. The homeland of Buttercup. You know – The Princess Bride. What if the cowardly Prince Humperdinck recognized and enforced patent, trademark, copyright and trade secret concepts as seen in that movie? Inconceivable, you say? But what would that look like and what would be some examples?

[If you have never seen The Princess Bride, kindly stop reading and go watch it. Now. I do not think I can be friends with anyone who does not like this movie.]

I will skip the kissing parts and go right into the action and adventure. Pirates are cool, right? To the land of Florin we go!

1. “As you wish” – service mark?

Westley’s trademark response to Buttercup’s requests. Unfortunately, I use “trademark” more in a colloquial sense, as Westley does not appear to use “as you wish” to identify the source of goods or services and it is unlikely to be something he uses in commerce. According to the USPTO:

A trademark is a brand name. A trademark or service mark includes any word, name, symbol, device, or any combination, used or intended to be used to identify and distinguish the goods/services of one seller or provider from those of others, and to indicate the source of the goods/services.

While Westley’s three word slogan of sorts may identify his personal services to Buttercup, but it does not appear to rise to the level of a protectable trademark or service mark in the classic sense.

2. The symbol of Guilder – collective trademark

After Vizzini and his crew kidnap Buttercup, he explains to Inigo Montoya that he is putting a symbol of Guilder – Florin’s sworn enemy – on a piece of Buttercup’s dress. The purpose is to indicate to any search party that Guilder is to blame. This is a diversionary tactic, but it demonstrates the value of famous trademarks and symbols. This particular symbol brings a source-identifying status to the nation of Guilder. It therefore acts as a collective trademark, indicating a “regional origin” that is subject to 15 U.S.C. § 1054.

3. The “Cliffs of Insanity” – regional trademark

Such a mystery. Who coined the term “The Cliffs of Insanity”? The Cliffs of Insanity can be found on the Guilder side of the Florin channel. It is well-known landmark of Guilder. Nevertheless, we can reasonably assume that this is not the formal name of the land, thereby making it a nickname that might rise to the level of a protectable trademark pursuant to 15 U.S.C. § 1052, so long as it is distinctive to customers in that region. For such a strong name, there must be more of a backstory. Alas, we are not given much more of the history of this particular landscape. Maybe in the inevitable sequel.

4. Westley’s mask – trademark / trade dress / publicity rights

While Vizzini and Fezzik leave Inigo behind to deal with the mystery man behind them, Fezzik warns Inigo that “people in masks are not to be trusted.” Westley’s black mask has become his identifying trait. While at this point in the movie no one has connected the mystery man to the Dread Pirate Roberts, it could also be the known outfit or uniform of the famous pirate. Later, when Fezzik battles Westley, he asks why he is wearing a mask. Westley responds by saying that it is “terribly comfortable” and that everyone should be wearing them.

The mask itself could be a trademark of the Dread Pirate Roberts. The aesthetic nature of the mask could be famous in Florin and Guilder and a reasonable person might mentally connect masks with the well-known pirate. This would be a source-identifying mark. Even pirates have the right to protect their image. If Florin adopted Texas law on publicity rights, the Dread Pirate Roberts or Westley could protect his image for up to fifty years after his death. See Tex. Prop. Code § 26.003(2). (This Texas statute is commonly known as the Buddy Holly Law.)

In contrast, Westley does mention the functional aspects and benefits of the mask. Trademark law does not protect the functional aspects of marks. Pursuant to 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(5), functional trademarks cannot be registered on the Principal Register. Westley would have to claim solely on the distinctive image of the mask, and therefore not the functional aspects of it.

5. Inigo Montoya’s father’s sword – copyright / trade dress

Inigo Montoya is proud of his father and his father’s handiwork. In particular, Inigo brags to Westley about his father’s sword, which was originally commissioned by the Six Fingered Man, but now is in the possession of Inigo after the Six Fingered Man only wanted to pay 10% of the asking price. When he presents it to Westley to examine, Westley confirms that he “has never seen its equal.” The unique design of Inigo’s sword is therefore protected as a copyright, as it is an original work of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression. 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). Much like Westley’s mask, however, there are functional aspects of the sword we are all familiar with. Similar to trademarks, the functional aspects of a copyrighted work are not protectable. These aspects of a “useful article” are restricted from enforceability as a copyright pursuant to 17 U.S.C. § 113(b).

Inigo’s father would be the author of this copyright and upon his death the copyright would likely have passed to his son, as set forth by 17 U.S.C. § 201(d)(1). Notably, the sword was originally commissioned for Count Rugen’s benefit. Count Rugen being a naturally cruel person would likely sue Inigo and claim that this custom-made sword was a “work made for hire” and that he is the rightful owner of all copyrights in the sword, even if he never paid for the finished work. 17 U.S.C. § 201(b).

6. Sword-fighting strategies – trademark? Business method patent?

During their sword fight, Inigo and Westley describe four sword fighting techniques and strategies (Bonetti’s Defense, Capo Ferro, Thibault, and Agrippa). Interestingly, these are actual techniques for sword fighting. While these are common terms and strategies for sword fighting, the names are unlikely to be protected by trademark law. Similar to how the “West Coast Offense” strategy in American football is not a protectable trademark, even if you can tie each strategy back to its originator. Nor are these methods subject to a patent. While they are specific methods with steps of these strategies, the inventor has failed to restrict the public use of these methods and each is now in the public domain. Patent law protects patented inventions for only twenty years after the date the inventor files an application for a patent. 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(2).

7. Fezzik’s “Way” – business method patent?

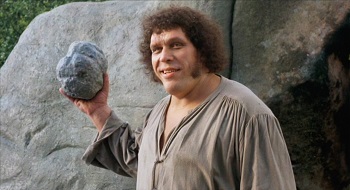

Vizzini instructs Fezzik to fight the Man in Black “your way.” Fezzik quizzically asks “what’s my way?” only to be informed the specific steps of his “way”:

Pick up one of those rocks, get behind a boulder, in a few minutes the man in black will come running around the bend, the minute his head is in view, hit it with the rock.

Fezzik concludes that his way is not very sportsmanlike. But is it patentable? It definitely is a method with specific, discrete steps. Pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 101, it may even have a specific, substantial and credible utility. Even though Fezzik’s method is inherently dangerous to the lives of others, namely Westley, it might still be patentable. Considering the nature of this method, however, the government of Florin would likely step in and declare Fezzik’s way to be secret and not subject to public disclosure, even if he filed a patent application. See generally 35 U.S.C. § 181 (Invention Secrecy Act of 1951). Fezzik’s method could be classified alongside nuclear technology or bio-weaponry. Even Westley is a believer in the utility of Fezzik’s method. Fortunately, Fezzik prefers sportsmanlike encounters.

8. Iocaine Powder – patent

Westley describes iocaine powder as “odorless and tasteless” and also one of the more deadly poisons originating from Australia. Is it patentable as a chemical compound? If it occurs in nature, it is not patentable. Pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 101, it would not be new composition of matter. According to the U.S. Supreme Court, it also would not be patentable if the inventor merely isolated this chemical from its naturally occurring state. See Ass’n for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 133 S. Ct. 2107 (U.S. 2013). Iocaine powder could be the naturally occurring version of sodium fluoroacetate, which would negate patentability.

If, however, iocaine powder is not naturally occurring but is derived from other naturally occurring chemical or pharmaceutical compositions, it could be patentable under 35 U.S.C. § 101 as being novel and non-obvious, even if it is one of the more deadly poisons known to man.

9. The “Dread Pirate Roberts” – trademark / trade name / collective mark

Throughout the movie, the name “Dread Pirate Roberts” is used to invoke fear. Westley is initially captured by the Dread Pirate Roberts and taken hostage on his ship Revenge. Buttercup then identifies the Man in Black as the Dread Pirate Roberts. Westley later explains to her the origin of the name and the history of those who have used the name. Westley even succinctly summarizes the purpose of trademark law in his story. The name is what matters. “No one would surrender to the Dread Pirate Westley!”

Yet Westley concedes that he is not really the Dread Pirate Roberts. He is just the current titleholder to the name. How does this work under trademark law?

The name itself should be subject to a trademark or service mark, as it is a brand name “intended to be used to identify and distinguish the goods/services of one seller or provider from those of others, and to indicate the source of the goods/services.” It should therefore satisfy the requirements of 15 U.S.C. § 1127. What if there are multiple users of the same mark? Can this collective claim equal rights in the name? According to the law, yes. To the extent each of the known current and/or former Dread Pirate Robertses each recognize each other as members of a collective or organization, they may each claim rights to use the mark. To be a collective mark, the law requires only the following:

The term “collective mark” means a trademark or service mark (1) used by the members of a cooperative, an association, or other collective group or organization, or (2) which such cooperative, association, or other collective group or organization has a bona fide intention to use in commerce and applies to register on the principal register established by this [Act], and includes marks indicating membership in a union, an association or other organization. 15 U.S.C. § 1127.

To the extent the name “Dread Pirate Roberts” is a collective mark, it is not owned by any individual member, but is instead owned by the collective and used by its members. See Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1302.

10. The Machine – patent

The impetus for this article. Count Rugen is proudly compiling notes on a personal torture study (#11 below). To assist in his studies, he has invented what he calls “The Machine.” Sadly, this may be the worst trademark of a product as it is merely descriptive or generic, but I will ignore that for now. The Machine is quite an invention. It is novel and non-obvious and it has utility. Pursuant to 35 U.S.C. § 101, it meets all of the definitions of patentability.

Even more interesting is that The Machine can be claimed as both a utility patent and a method patent. The physical invention itself is the utility patent or product while the method for sucking years of life from a subject is a separate invention. Additionally, it seems he is not finished tweaking his invention as he has yet to test it to “5” yet. His private experimental use may also allow him to avoid the one-year window of time to file a patent application. 35 U.S.C. § 102(b).

Count Rugen may be cruel but he also appears to be very smart and scientific. A true evil genius. He even gives the audience a synopsis of the prior art that led to this invention:

As you know, the concept of the suction pump is centuries old. Really that’s all this is except that instead of sucking water, I’m sucking life. I’ve just sucked one year of your life away. I might one day go as high as five, but I really don’t know what that would do to you. So, let’s just start with what we have. What did this do to you? Tell me. And remember, this is for posterity so be honest. How do you feel?

Count Rugen calmly explains that he has taken a known concept (the suction pump) and created something novel from it. Given his scientific acumen, why Count Rugen felt the need to commission Inigo’s father to make him a sword remains a mystery. The Machine is quite a work of art, and it appears to work at level “50” too, as Prince Humperdinck demonstrated.

11. Count Rugen’s unfinished (and untitled) torture study – copyright

Count Rugen explained to Westley that he is working on the “definitive work on the subject” of human torture. Presumably, Count Rugen has been working on this for years and Westley was not his first subject. The notes and any writings Count Rugen may have compiled on this study are protected by copyright law. The moment Rugen committed pen to paper it became copyrighted. Pursuant to the statute, a work is “fixed” in a tangible medium of expression when it “is sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration.” 17 U.S.C. § 101. Unless Count Rugen is compiling this study in his role as an employee of the government (as the government cannot be the author of copyrighted works, 17 U.S.C. § 105), his writings are definitely subject to copyright protection even if the work is unfinished (thanks to Inigo) and likely will never be published.

12. Miracle Max’s potion pill – trade secret / patent

Miracle Max was fired by the King’s stinking son, Prince Humperdinck. That means he no longer works for the government. Usually an employee has a duty to assign patent rights to his employer, but Max is now an independent contractor only performing miracles for substantial sums of money or in instances of noble causes. Much like The Machine, Miracle Max’s pill to revive the mostly dead is patentable subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101 and he could seek to exclude others – especially his replacement at the castle – from performing his miracles. The step of dipping the pill in chocolate syrup would naturally be a dependent claim to any invention he discloses.

Max is a proud and private man, however. He may have kept all of his miracle methods secret and would not want to publicly disclose any of his knowledge through a patent application. He could keep all of his knowledge as a trade secret, though his wife may inadvertently disclose a secret or two without his permission. Now that Humperdinck has been subjected to “humiliations galore,” Max may no longer feel the need to prove anything to anyone. His secrets will most likely die with him.

13. The Impressive Clergyman’s wedding speech and song – copyright

The Impressive Clergyman overseeing the wedding of Humperdinck and Buttercup prepared a lengthy speech on marriage and true love. He even wrote and sang a song. This was a public performance of a copyrighted work. As set forth by the copyright law:

To perform or display a work “publicly” means (1) to perform or display it at a place open to the public or at any place where a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is gathered; or (2) to transmit or otherwise communicate a performance or display of the work to a place specified by clause (1) or to the public, by means of any device or process, whether the members of the public capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same place or in separate places and at the same time or at different times.

Even though Humperdinck rudely demanded that he “skip to the end,” the Impressive Clergyman’s speech and song is copyrighted and was published by his public performance. While the wedding itself may not have happened due to a technicality, the speech was performed and is subject to copyright protection.

14. Other potential examples of intellectual property rights

In no particular order: the 500th anniversary of Florin City (slogans and logos that could be a trademark), the secrets of the Fire Swamp (trade secrets), ROUSes (potentially patentable as genetic mutations, but I do not believe they exist), the Pit of Despair (trade name for a business), the Brute Squad (trademark or collective mark), “the Man in Black” (could be a trade name but it was never used by Westley himself, so it is unlikely to be enforceable by him), Inigo Montoya’s mantra (“My name is Inigo Montoya; You killed my father; Prepare to die” – may be subject to copyright protection as it is more than a simple word or phrase).

I will stop here before we get to more kissing parts. I hope this trip through the fantasy world of Florin helped make the understanding of intellectual property rights easier to understand and perceive. If you have any questions or additional comments on this topic or the movie, I am easier to locate than the Six Fingered Man – david@law-dlc.com.

Have fun storming the King’s Castle!

Recent Comments