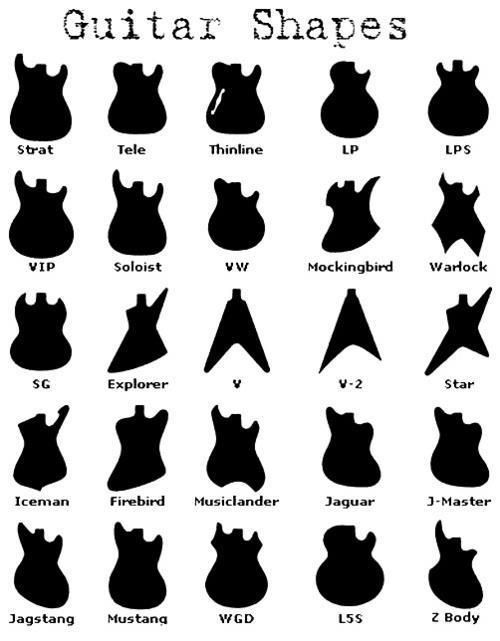

In May 2019, Gibson Brands, Inc. sued Armadillo Distribution Enterprises, Inc. for trademark infringement, unfair competition, and counterfeiting.[1] Armadillo may not be a well known name, but it is affiliated with the guitar brands Dean Guitars and Luna Guitars, which compete with Gibson. Gibson is one of the most prominent names in the electric guitar industry, alongside Fender. In this lawsuit, Gibson accuses Armadillo/Dean of infringing at least four “body shapes” of its electric guitar models: the Flying V, the Explorer, the ES, and the SG, each of which Gibson cites as a registered trademark.[2]

This case caught my attention because I am a guitar player and I often write about music and the music industry as it relates to trademarks and copyrights. Here are just a few examples. I do not personally own any Gibson-branded guitars (they are too heavy in the neck), but I do own one acoustic Dean Guitar – though not one of the types that is accused of infringement in this case. With regard to electric guitars, I prefer Schecter Guitars. Always a Hellraiser™.

Armadillo has not yet responded with an Answer to this lawsuit, but I anticipate Dean Guitars will present a substantial defense to all of Gibson’s claims. It is important to note that this is not a patent case. This is not about who “invented” the particular shape or style of an electric guitar. Any patent rights for these designs would have expired decades ago. Instead, this dispute concerns trademarks. It essentially seeks to determine whether a particular shape of a guitar evokes a specific source in the minds of the relevant consuming public. With regard to the guitar industry, there is a long history associated with these particular “body shapes” and how they impact pop culture and the competition between the most popular brands and manufacturers.

History of Gibson’s Electric Guitar “Body Shape” Trademarks

According to the lawsuit, Gibson has acquired trademark registrations for each of the specific “body shapes” of the electric guitar models at issue:

- The Flying V (U.S. Trademark Reg. No. 2051790 – first use 1958)

- The Explorer (Reg. No. 2053805 – first use 1958)

- The ES (Reg. No. 2007277 – first use 1958)

- The SG (Reg. No. 2215791 – first use 1961)

Gibson did not acquire these trademark registrations until the 1990s, however. Nearly forty years after the alleged “first use” of these specific body styles in the industry. Nevertheless, Gibson is not tasked with proving that it invented the body style. It merely needs to show that it was the first to continuously use these body styles in the industry and that the relevant public identifies these body styles with Gibson itself. This is because trademark infringement is determined from the consumer’s viewpoint as the purpose of trademarks is to identify the source of goods to the public.[3] Trademarks rights exist to protect the public interest.[4]

Notably, even if it did not acquire the registrations until the 1990s, Gibson may still have acquired “common law” trademark rights which attached the moment these uses began.[5] Trademarks can be enforced without a registration, though registration is often encouraged for many reasons. In fact, “common law” infringement is among the causes of action asserted by Gibson in this case. This is a viable legal claim in Texas.

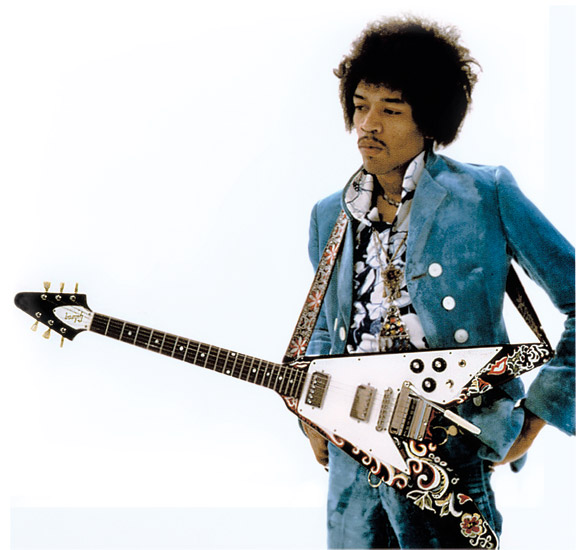

The primary question I have, however, is this: do these body shapes evoke the name “Gibson” in the minds of the consuming public? I am a guitar player, and I am quite familiar with Gibson guitars and the Gibson® brand. But when I think of the Flying V, I think of Jimi Hendrix or Eddie Van Halen. Interestingly enough, Jimi was mostly affiliated with Fender guitars.

When I think of the Explorer guitar model, I think of James Hetfield of Metallica.

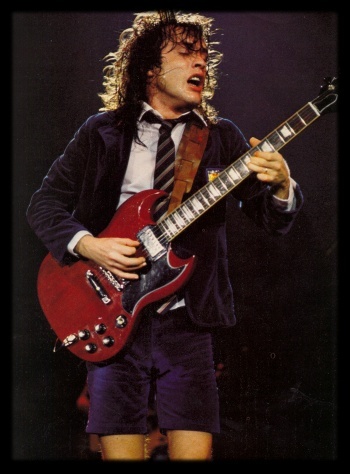

When I think of the SG model of guitar, there is only one obvious answer: Angus Young of AC/DC.

Among music fans and guitar aficionados, these guitar shapes are often affiliated with specific rock stars and not as much the brands or the manufacturer.[6] Sure, I recognize certain models as a “Gibson” guitar based on the totality of the fretboard markings, the headstock, and the Gibson® label and name printed on the guitar itself. From a distance, however – that initial impression may not be there. There is a reason for this. It is because Gibson is not the only brand that makes guitars that have these body shapes and styles.

Gibson has sued Dean Guitars over the trademark to these body shapes, but there are extensive third-party uses of these styles. And these uses have been commonplace for decades.

Third-Party Uses of Same “Body Shape”

Gibson’s claim that it owns four trademark registrations for these four specific body shapes is a factual statement. It does own these trademark registrations. This does give it a rebuttable presumption of validity and enforceability at trial.[7] But the key word here is “rebuttable” as any presumptions of validity can be overcome through various factors that would demonstrate that the “body shape” fails to function as a source-identifier in the marketplace.[8]

If there are substantial unchecked third-party uses of a trademark in commerce, this may weaken the protection for a specific trademark.[9] These uses would lend credence to a claim that these body styles have become commonplace and maybe even “generic” within the industry.

Where have these other body shapes been used by competing guitar brands?

The Flying V

There are many brands that sell or have sold a “Flying V” body style. Among them are BC Rich, Jackson Guitars, Ibanez Guitars, Kramer, and even Schecter.

The Explorer

There are also many brands that sell the Explorer-style model (just under a different name at times). Once again, this includes Schecter, Jackson, and Ibanez, among others.

The same analysis can readily be conducted for the ES and SG models. These are “stock” shapes and models throughout the industry. Gibson may have been the first to use and market these specific styles, but over the last 60-70 years, they have become ubiquitous across all brands and makers, with only the slightest of variations. Gibson’s Complaint alleges that “[a]s a direct result of Gibson’s promotional efforts and extensive sales, the Gibson Trademarks have been prominently placed in the minds of the public.”[10] But the evidence suggests the name of the shape has become predominant, while any specific “brand” association has been lost in the mix.

Nor is Gibson an innocent bystander of this shape appropriation. Gibson itself sells and/or has sold “body shapes” that mimic other brands’ iconic guitars. Most recently, Gibson proposed its own version of a Stratocaster – a body style most commonly associated with Fender, its biggest competitor. This is not to say that Gibson is being hypocritical necessarily. This merely demonstrates that it is not uncommon for a guitar manufacturer to use other well-known body styles, even if another brand first popularized it.

Which leads me to the next issue: are these body styles legally “generic”?

Trademark Genericide

“Generic” marks (including generic trade dress) are not enforceable as trademarks. In trademark law, a generic term “refers to an entire class of products (such as ‘airplane’ or ‘computer’), does not distinguish a product at all, and therefore receives no protection under trademark law.”[11] With regard to standard word marks, this includes things like ASPIRIN or ZIPPER or the like.

In the context of a guitar body shape – does a particular style or shape distinguish a product? Or can one particular body shape refer to an entire class of products bearing that shape which are marketed and sold by a multitude of various guitar manufacturers? At one point in time, the Flying V, the Explorer, the SG, and the ES may have been wholly intertwined with the Gibson® brand. Trademarks are fluid concepts, however. What was protectable as a trademark 60 years ago is not necessarily protectable today by default.

This is the concept of “genericide.” Genericide can occur when a protected mark, over time, becomes the shorthand name for an entire genus of products sold under it.[12] For example, the word “escalator” was once a protected trademark. The same for YO-YO. Over time, these just became the common words for the entirety of that product line. It is why I often correct people who casually use the trademark “Xerox” to refer to the entire process of making a photocopy. Xerox® is a trademark that does not apply to all photocopy companies and processes. Unlike Gibson, the Xerox Corporation has made a concerted effort to make sure that its valuable trademarks did not fall prey to “genericide.”

Gibson, meanwhile, claims first use of these “body styles” dating back to 1958, but did not apply for federal trademark registrations until the mid-1990s. Subsequently, Gibson has potentially not been proactive in educating the public that these certain body styles belong to Gibson. This is how extensive third-party uses become commonplace. This is how genericide happens.

A trademark owner has an informal duty to police its alleged trademarks in commerce.[13] This is tied to a legal proposition known as “laches” – if you delay too long in enforcing trademark rights against a person or entity you believe to be infringing your trademark, you may lose the right to enforce that trademark.[14] This analysis is done on a case-by-case basis.

Gibson’s Amended Complaint against Dean Guitars asserts that Gibson’s lawyers sent a cease-and-desist letter to Armadillo on October 20, 2017 and again on May 13, 2019. This followed a prior legal proceeding between the parties over trademark rights dating back to 2006.[15] Dean Guitars and many other third-parties in the industry have been making, offering, and selling similar “body shapes” to the consuming public long before 2017, or even 2006. Gibson has been well-aware of these other extensive uses.

This lawsuit also accuses Dean and Luna of making counterfeit guitars. This is a curious allegation to make given the nature of the guitar industry as we have discussed. It also may not comport with what constitutes a legal counterfeit by definition.

“Counterfeit” Body Styles of Guitars

Under United States trademark law, a “counterfeit” is defined as “a spurious mark which is identical with, or substantially indistinguishable from, a registered mark.”[16] For a plaintiff to prevail on any counterfeit claim, it must show that the defendant(s) “infringed a registered trademark in violation of 15 U.S.C. § 1114(a)(1) and also that they “intentionally used a mark … knowing such mark … is a counterfeit mark.”[17] Counterfeiting is a big problem.

But when I think of what is a “counterfeit” – I think of fake Rolex® watches or fake shoes or handbags for women.[18] The idea being that a person seeing these counterfeits would not readily identify them as being from a source other than the famous brand name. The central distinguishing feature being that the infringing party knows it to be a counterfeit and intends on the consuming public to be fooled by the false designation of origin.[19]

In contrast, Dean Guitars is not selling Flying V models with the “Gibson” name on the headstock or the body. There are no substantiated allegations that any advertisements from Dean Guitars operate to suggest, imply, or indicate that the guitar model being sold is affiliated with or licensed by Gibson. Instead, the “Dean” insignia and its own distinctive trademark are conspicuously present on the headstock and the packaging.

This is not a counterfeit. No reasonable purchaser of this product would think that they are buying a Gibson®-brand guitar.

Other Potential Defenses to Infringement

This case presents a voluminous amount of law school hypothetical style issues under the umbrella of trademark law, patent law, unfair competition, trademark dilution, tortious interference, and other causes of action. I have tried to address the obvious issues relating to third-party uses, genericide, counterfeiting, and failure to function (i.e. is this body shape even a ‘trademark’ that identifies the source of goods?). There are many other viable defenses that Dean Guitars is likely to present to the Court. These include:

Implied license

Even if the parties intend no formal licensing agreement, “in some circumstances … the entire course of conduct between a … trademark owner and an accused infringer may create an implied license.”[20] The essential inquiry is whether the right granted by the subject agreement permits an infringing use of the license.[21] Gibson has been aware of third-party uses of these “body shapes” for decades, even while it held trademark registrations for same. Dean Guitars was certainly aware of Gibson’s own body shapes. Other third-party users were aware of Gibson as well. There are many guitar manufacturers, but there are really only 10-20 brands that can readily be found at a Guitar Center-type store or warehouse. Everyone is familiar with everyone else’s product line.

Gibson was certainly aware of Dean Guitar’s own body shapes, styles, and designs. Gibson’s own Complaint even states that there was a prior trademark opposition proceeding in 2006, and which ended in 2009. Yet Gibson took no direct legal action for a decade after that was resolved. Based on the prior relationship between the parties, Dean Guitars could have reasonably construed that Gibson implicitly granted a right to use these body shapes so long as they were not likely to confuse the public.

Abandonment

Did Gibson effectively abandon its trademark rights by allowing these third-party uses to permeate the marketplace? This is related to Gibson’s failure to police the mark as well. An abandoned trademark is “fair game for any merchant or manufacturer who seeks to use it.”[22] To prevail on a claim for cancellation of a trademark registration on the ground of abandonment, a party must allege and prove abandonment of the trademark as the result of nonuse with intent not to resume use. The burden of proof is on the party claiming abandonment.[23] This is a high burden and Dean Guitars is almost certain to not prevail on this theory because Gibson is still using these body styles and has not overtly announced any intention to cease the use of same.

Of course, if Dean Guitars is able to demonstrate that the body shape trademarks are generic then that effectively abandons any claim Gibson can make for infringement. Generic marks are never enforceable as trademarks.

Failure to Function as a Trademark

This is an interesting theory. If the body shape does not indicate “Gibson” as the source of a specific guitar manufacturer/brand, then the shape fails to fulfill any purpose as a trademark and therefore would not be enforceable. “The primary function of a trademark is to serve as a label–a mark that identifies and distinguishes a particular product.”[24] Like abandonment theories, this is also tied to the concept of genericide. If an alleged mark no longer serves the basic features of a “trademark” – it can no longer be enforced as a trademark by the purported owner.

No Likelihood of Confusion

This is the crux of the dispute. And while I do not mean to bury the most important issue at the end of this article, I address it here only because it is more of a nebulous concept at this stage of the proceedings.

Trademark infringement cases are decided based on a likelihood of confusion. That is the standard. But it is a multi-factor test that is a case-by-case analysis that requires an evaluation of all of the evidence. In consideration that this case has only just begun and evidence such as surveys regarding consumer recognition have not yet been offered, to opine on whether there is a likelihood of confusion as a “yes” or “no” proposition would be unfair.

Generally speaking, however, are guitar players confused by the existence of Gibson’s Flying V versus Dean Guitars’ own version of a Flying V? I would posit “no” on that point. Most purchasers of a guitar, especially a Gibson (which is a high-priced product), are “sophisticated” purchasers. This is one of the likelihood of confusion factors to consider. It is highly unlikely that they would confuse a Dean guitar for a Gibson guitar when they walk out of a store.

Additionally, there are no allegations and so far no evidence on the record to suggest that there is any evidence of “actual confusion” in the marketplace. Again, this is not surprising because guitar players are unlikely to be confused based solely on body shapes that have likely become somewhat commonplace over time.

Additional Considerations / Conclusions

I do not think this case is as strong as Gibson’s attorney presents it to the Court. Gibson’s representatives already took down a video they posted to YouTube as a “warning,” presumably after the lawyer advised them to tone it down. At least I hope that was the reason. Gibson’s “legacy” is not as iconic as it used to be, and the company has been treading water and is in a post-bankruptcy period where its reputation is still in recovery. This may not help.

In the end, I think Gibson waited too long to pursue claims for trademark infringement. This is a potential classic case of genericide that has been building for over 50 years. These body styles have become so standardized over time that the average guitar player would not necessarily associate a particular shape with “Gibson” alone. Even the terms “Flying V” and “Explorer” are used casually and generically by those in the industry and not necessarily in conjunction with the Gibson® name or brand.

The most curious fact of this case is that Gibson filed the

lawsuit in Texas. Gibson Brands, Inc. is a Delaware corporation with a

principal place of business in Tennessee. Its connections to Texas are tenuous

at best. Meanwhile, as of today, there is only one lawyer identified as counsel

of record for Gibson in this case. This lawyer is a solo practitioner from Waco

and his website identifies him as an “estate planning” lawyer – not a trademark

or IP law specialist. Trademark law is incredibly nuanced and specialized and

this could backfire spectacularly on Gibson if its litigation counsel is not

adequately experienced in trademark law.

[1] Gibson Brands, Inc. v. Armadillo Dist. Enters., Inc., No. 4:19-cv-00358-ALM (E.D. Tex. May 2019) (Amended Complaint filed June 6, 2019).

[2] Gibson is also accusing Armadillo of infringing a specific headstock and two word marks (HUMMINGBIRD and MODERNE), but these are mostly ancillary to the primary claims in the Amended Complaint.

[3] Waples-Platter Cos. v. Gen. Foods Corp., 439 F. Supp. 551, 573 (N.D. Tex. 1977).

[4] TGI Friday’s, Inc. v. Great N.W. Rests., Inc., 652 F. Supp. 2d 763, 773 (N.D. Tex. 2009).

[5] Emerald City Mgmt., LLC v. Kahn, No. 4:14-cv-358, U.S. Dist. LEXIS 106674 (E.D. Tex. June 19, 2014).

[6] I find the “ES” model to be relatively ugly and not a body style I affiliate with any particular player or maker.

[7] See generally 15 U.S.C. § 1115(a).

[8] El Chico Rests. of Tex., Inc. v. Mexican Inn Ops. #2, Ltd., No. 3:09-cv-2294-L, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 44932, at *14-17 (N.D. Tex. March 30, 2012).

[9] Quantum Fitness Corp. v. Quantum Lifestyle Ctrs. LLC, 83 F. Supp. 2d 810, 820-21 (S.D. Tex. 1999).

[10] Gibson’s First Amended Complaint, at ¶ 24.

[11] Sport Supply Group, Inc. v. Columbia Cas. Co., 335 F.3d 453, 461 (5th Cir. 2003).

[12] March Madness Ath. Ass’n v. Netfire, Inc., 310 F. Supp. 2d 786, 808 (N.D. Tex. 2003).

[13] Armco, Inc. v. Armco Burglar Alarm Co., 693 F.2d 1155, 1161 (5th Cir. 1982)

[14] York Group, Inc. v. York Southern, Inc., No. H-06-0262, 2006 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 73743 at *7-9 (S.D. Tex. October 10, 2006).

[15] Gibson’s First Amended Complaint, at ¶ 34.

[16] 15 U.S.C. § 1127.

[17] 15 U.S.C. § 1117(b); see also Interstate Battery Sys. of Am. v. Wright, 811 F. Supp. 237, 243-44 (N.D. Tex. 1993).

[18] See generally Rolex Watch U.S.A., Inc.v. Zolotukhin, No. 3:14-cv-2867, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 43129 (N.D. Tex. March 31, 2016).

[19] Springboards to Educ., Inc. v. Kipp Found., 325 F. Supp. 3d 704, 717 (N.D. Tex. 2018) (“This court has interpreted a trademark counterfeit claim to operate as a trademark infringement with the addition of a defendant’s intention to use the plaintiff’s trademark, knowing it was a counterfeit.”)

[20] Exxon Corp. v. Oxxford Clothes, Inc., 109 F.3d 1070, 1076 (5th Cir. 1997).

[21] Id.

[22] Acme Valve & Fittings Co. v. Wayne, 386 F. Supp. 1162, 1167 (S.D. Tex. 1974).

[23] 15 U.S.C. § 1127; Vais Arms, Inc. v. Vais, 383 F.3d 287, 293 (5th Cir. 2004).

[24] Sport Supply Group, 335 F.3d at 461.

Recent Comments