Alfonso Ribeiro sues video game makers over the “Carlton Dance”

December 19, 2018

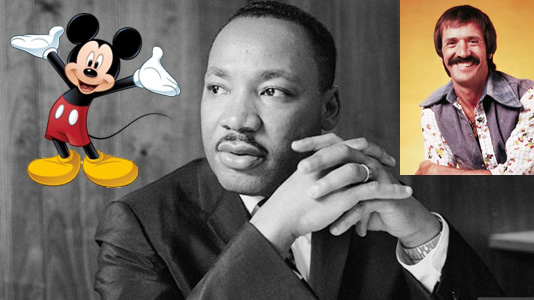

On Monday, December 17, 2018, Alfonso Ribeiro, an actor best known for roles on “Silver Spoons” and “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air,” filed two separate lawsuits regarding copyright and publicity rights associated with what is colloquially known as the “Carlton Dance.”[1] Ribeiro sued the makers of the popular Fortnite and NBA2K games for their allegedly unauthorized uses of this dance choreography. His causes of action are based on copyright infringement, violation of publicity rights (California state law), and state and federal unfair competition claims.

The lawsuit(s) begin by asserting that Ribeiro is “an internationally famous Hollywood star, known for his starring role as Carlton Banks from the hit television series The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and as host of America’s Funniest Home Videos. Ribeiro created his highly recognizable “Dance,” that has also been referred to by the public as “The Carlton Dance,” which exploded in popularity and became highly recognizable as Ribeiro’s signature dance internationally. The Dance is now inextricably linked to Ribeiro and has continued to be a part of his celebrity persona.” The lawsuits later allege that “The Dance has become synonymous with Ribeiro.” In short, these assertions are wildly debatable. Given the national attention this case has received, I would like to look at some of the legal issues raised by these lawsuits and address the possible and likely defenses to Ribeiro’s claims and contentions.

Recent Comments