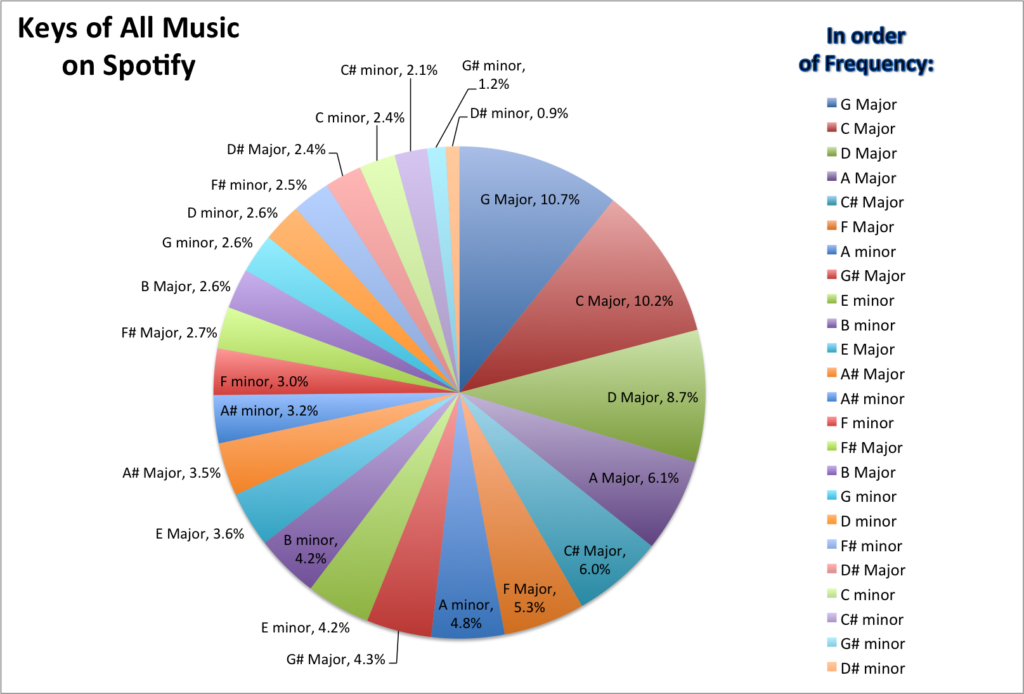

It has long been a running joke that if you only know how to play the G, C and D chords on a guitar, then you already know how to play hundreds of different popular songs. Many musical acts have been ridiculed for only playing the same three chords over and over. “Three-chord” rock music is practically its own genre. The I-IV-V major key chord progression is even considered the “standard” blues progression. Within that construct, there are only 12 basic “notes” or tones in the musical spectrum: A, Bb, B, C, C#, D, Eb, E, F, F#, G, and G#. From there it is just a matter of octaves to achieve different ranges of an “A” note. In short, there is a finite amount of discrete notes along with a relatively limited amount of chord progressions that are available to a songwriter.

Copyright law, meanwhile, only protects “original works of authorship” in musical works and sound recordings.[1] It is right there in the statute: the song or sound recording must be original. Without the element of originality, there is nothing protectable under the law.

Knowing this, and with hundreds of years of the history of songwriting, are there any songs that are truly “original” anymore? Is there any progression or riff that is so unique as to stand apart from every song that has been previously written? If not, how are musical works still subject to claims of copyright infringement and why should we care?

Popular Music Copyright Cases

There is a litany of copyright disputes over musical works. Led Zeppelin has recently been accused of infringement, as have a number of other acts that have been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (*cough*Green Day*cough*). The most famous copyright infringement case involves one of the Beatles – George Harrison.[2] Harrison was found to have “subconsciously” plagiarized the song “He’s So Fine” in his recording of “My Sweet Lord.” The result of being found liable for copyright infringement purportedly put Harrison in such a funk that he was “paranoid” to write any new songs for a lengthy period of time.

More recently, the summer anthem of 2013, “Blurred Lines” was found to be an infringement of a Marvin Gaye hit from 1977. To the tune of over $7 million in damages awarded by the jury (a number that has since been appealed).

While the Harrison case may be the most famous and the recent “Blurred Lines” dispute the most recently infamous, here are a few other noteworthy music copyright infringement disputes:

- Queen and David Bowie (“Under Pressure”) v. Vanilla Ice (“Ice, Ice Baby”)

- Gordon Jenkins (“Crescent City Blues”) v. Johnny Cash (“Folsom Prison Blues”)

- Huey Lewis (“I Want a New Drug”) v. Ray Parker (“Ghostbusters” theme)

- The Rubinoos’ (“I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend”) v. Avril Lavinge (“Girlfriend”)

- The Rolling Stones (“The Last Time”) v. The Verve (“Bittersweet Symphony”)

- Many, many, many more.

It is not a short list. Even my personal favorite band found itself at the heart of a plagiarism allegation in the underground music scene. Nirvana’s “Negative Creep” admittedly does have a very similar chorus to Mudhoney’s “Sweet Young Thing Ain’t Sweet No More.” The fact that both bands were from the Seattle scene (and not world famous yet) only made the allegation a bit more painful.

And just recently, Justin Bieber – of all people – has had to fight back against allegations of copyright infringement for a simple “ooo-ooo-ooo” vocal arrangement in his song “Sorry” (how apropos). Taylor Swift even had to “shake off” recent copyright infringement claims, with the help of a witty judge no less. Where does the madness end?

If you are a famous musician or recording artist, being the subject of plagiarism allegations and potentially a defendant in a copyright infringement matter just seems to be a rite of passage at this point. Why should it be this way? Is there any way to build a legal safe harbor and protect you from copyright claims as a songwriter?

Tests for Copyright Infringement

To prove copyright infringement, the person bringing the claim must prove two elements: (1) the ownership of a valid copyright, and (2) copying of constituent elements of the work that are original.[3] Assuming the ownership of a valid copyright, and where the defendant denies copying, one of the standard tests for determining infringement of original works is the “access” plus “substantial similarity” approach. It is a sliding-scale test, which means the more “access” you are shown to have, the less evidence of similarity is needed to demonstrate unlawful appropriation of the song. This test is most commonly performed by the Second Circuit (New York) in a step-by-step process. This is also known as the “copying plus unlawful appropriation” test, as mere copying is not sufficient to demonstrate infringement. There has to be that additional modicum of perceived wrongfulness to rise to the level of infringement.

In the case of Arnstein v. Porter, the Second Circuit held that to determine substantial similarity in musical works, courts must first apply the “ordinary observer” test.[4] Within that subset of the substantial similarity test, the plaintiff must prove that the villain copied or used “so much of what is pleasing to the ears of lay listeners, who comprise the audience for whom such … music is composed” to the extent one can conclude that it was “wrongfully appropriated” from the original songwriter and copyright owner.[5]

In cases where the song at issue is a mixture of original works combined with other “elements from the public domain” that are otherwise not protected by copyright, there is a more stringent test to be applied.[6] This test is the “discerning observer” test.[7] It requires the Court to compare the “total concept and overall feel” of the two songs with a focus on whether the alleged infringer “misappropriated” the original work based on how the original was “selected, coordinated, and arranged.”[8] At first glance, this is an overly complicated test that is inherently prone to the biases of the observer.

How Do I Avoid “Substantial Similarity”?

If you are a songwriter, or even a casual consumer of music, it is hard to challenge whether or not you had “access” to a song. Even George Harrison had to concede that he had indirect access to “He’s So Fine” when he was writing “My Sweet Lord.” Accordingly, even subconscious copying is not a defense to a copyright infringement claim.

This means that songwriters primarily need to avoid any “substantial similarity” with existing works. But we have already pointed out that there are only so many ways to construct a chord progression. There are only so many notes in the scale to pick from. With each new song being written and recorded, this reduces the number of available “original” ways to construct a song. It is quite possible that, absent changes in copyright law and enforcement, there can never be a safe harbor from “substantial similarity” claims by other songwriters.

Meanwhile, there are numerous studies that show that humans are pre-programmed to find certain chord progressions to be aurally pleasing.[9] It is why we routinely joke that “all songs sound the same” when there is actual evidence to support this hypothesis. There are actual algorithms that can predict whether a song will be received as a “hit” among the consuming public. If anything, this discourages originality. You can be certain that Clear Channel and other mass market radio stations are aware of these facts and program only those songs and playlists that are likely to garner the most attention from our ears. Thus, it is hard to be a successful musician if record companies, radio, and other popular distribution channels ignore you for ready-made commercial successes. The byproduct is that this may be a breeding ground for copyright infringement claims. It is a vicious cycle.

Accordingly, the title of this article may be misleading. I apologize. The question probably should not be “how” to avoid ‘substantial similarity’ and copyright infringement. The better question is likely “can” I avoid such allegations? And the answer is most likely: “no.”

[1] 17 U.S.C. §§ 102(2), (7).

[2] Bright Tunes Music Corp. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd., 420 F. Supp. 177 (S.D.N.Y. 1976).

[3] Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 361 (1991).

[4] 154 F.2d 464, 473 (2d Cir. 1946).

[5] Id.

[6] See generally Mayimba Music, Inc. v. Sony Corp. of Am., 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 152051, *39 (S.D.N.Y. August 19, 2014).

[7] Id. (citing Velez v. Sony Discos, 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 5495, 2007 WL 120686 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 16, 2007)).

[8] Edwards v. Raymond, 22 F. Supp. 3d 293, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 71482, 2014 WL 2158932, at *6 (S.D.N.Y. May 23, 2014).

[9] Spotify-data image from: https://spotifyinsights.files.wordpress.com/2015/05/keys.png

Recent Comments