As of this morning, there are seven (7) pending applications with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to register some variation of OK BOOMER as a trademark.[1] Thanks in part to the New York Times article in October, the casually dismissive phrase “ok, boomer” went from a limited internet audience to a mocking cultural term du jour. Inspired would-be entrepreneurs rushed to file applications with the USPTO to “own” this phrase as a trademark.

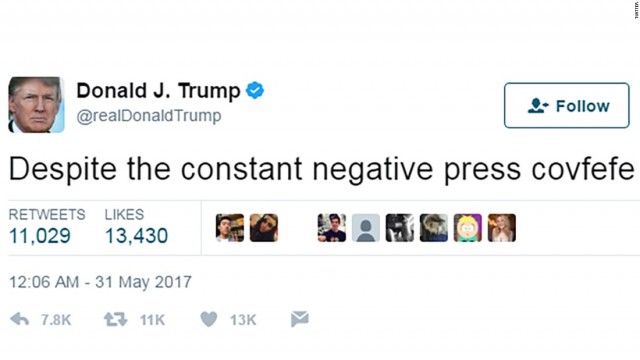

It is unlikely any of these applications will mature into a trademark registration. Simply put, this is not how trademarks work. Following in the footsteps of such whimsical terms like COVFEFE, TACO TUESDAY, and ALTERNATIVE FACTS, most of these alleged marks will fail to acquire a registration from the USPTO.

Because they almost certainly fail to function as trademarks.

What is a Trademark?

According to the USPTO, a trademark “is a word, phrase, symbol, and/or design that identifies and distinguishes the source of the goods of one party from those of others.” Similarly, a service mark “is a word, phrase, symbol, and/or design that identifies and distinguishes the source of a service rather than goods.” The most common examples of trademarks are brand names (i.e. NIKE®), slogans (“JUST DO IT®”), and logos (the SWOOSH). The term “trademark” is often used in a general sense to refer to both trademarks and service marks interchangeably.

Trademarks are only protectable if they are used in commerce in association with goods and services. This is because the law governing trademarks is derived from the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution.[2] Furthermore, the underlying purpose of a trademark is to help the relevant consuming public identify the source of goods. Trademarks are designed to benefit the public first. The “owner” of a trademark has quasi property rights only to the extent that the trademark is actively in use and operates as a source identifier. That is the trade-off.

This “use,” however, is not particularly defined. There must be something more than token use. This use must also constitute a veritable “trademark” use. The purported trademark must be used in a way that the relevant consumers would recognize and understand it to be a trademark.[3]

Commercial Use is Required

This is not patent law. Trademarks operate much differently. Most importantly, there is no “first one to file paperwork in the trademark office owns the word.” Nor can you outright “own” a word or phrase. Yet there is no requirement that you be the “inventor” of a term or phrase either. Trademark laws do not care who coined a term. Instead, it matters who and what the term was originally associated with from a commercial perspective.

For example, Kylie Jenner recently filed to register RISE AND SHINE and Twitter absolutely flipped out. But her application would not preclude anyone from saying the words “rise and shine” in association with basic daily activity. Jenner would not have a monopoly on the use of the words. You would not owe her royalties for using #riseandshine as a hashtag on your morning motivational Instagram story. This is not how trademarks work.

First, there is always the legal safe harbor of nominative and descriptive fair use. If saying the words “rise and shine” is reasonably necessary to describe an act or an event, you can fairly use the words without running afoul of trademark law. Second, Jenner is only claiming potential trademark rights to RISE AND SHINE in conjunction with certain types of clothing articles – a limited class of goods. The common phrase “rise and shine” is not intrinsically connected to clothing. Jenner therefore may be properly repurposing the term for a narrow commercial use. This is encouraged by trademark law. The primary difference at this stage is that Jenner has yet to demonstrate actual use in commerce of this mark in association with clothing (her application is an “intent to use” application at this stage). It is still hypothetical. It may not actually register as a trademark because it never matured into trademark use.

Kylie Jenner is not the only celebrity to file a series of random trademark applications.[4] Her intended uses, however, appear to have at least some semblance of a commercial purpose attached to them – which is entirely consistent with the purpose of trademark law.

In contrast, there is a logjam of pending applications for words, terms, and phrases that have no singular commercial purpose. This is where terms like OK BOOMER and COVFEFE entirely lose the trademark plot. Not that this has stopped a recent surge of non-celebrity applications seeking to register the latest popular phrase to reach the cultural lexicon. Please know you are wasting money on lawyers and filing fees and you are unlikely to ever “own” these words and phrases. I am writing this article to discourage this practice but to also try to explain why these terms typically cannot be trademarks to begin with.

Distinguishing “Trademarks” from Common Words and Phrases

Most any word, phrase, or logo can be a trademark. Even “common” words can be repurposed as trademarks – and used accordingly – so long as they function to identify a source of goods and services. To bookend the example of Kylie Jenner’s RISE AND SHINE application, the best example of this is APPLE®. The word “apple” is a common word for a popular fruit. It is well-known in that context. The difference is that “apple” has no common connection or association with technology or computers. Thus, the use of APPLE in that context creates a form of distinctive use. It is a valid and protectable trademark. It may be the most valuable trademark in existence today.

By way of contrast, if you started a company selling fruit, you would likely fail to distinguish your company if you tried to name it “Apple.” Because this is the common (or generic) form of the term for the type of goods you are theoretically selling. It would also fail to identify the source of your specific goods from that of a competitor. Thus, not only would it lack distinctiveness, but it would fail to function as a trademark to identify goods and services. This is known in trademark law as a “generic” mark. Generic marks are never protectable as trademarks. They inherently fail to function because they are “terms that the relevant purchasing public understands primarily as the common or class name for the goods or services” and they are incapable of denoting a source of goods.[5]

As an inelegant rule of thumb, if a term or phrase does not conjure up a mental image of a particular good or service, it is not being used as a trademark. It can become a trademark through use in commerce and acquiring the necessary distinctiveness in association with certain goods and services though. That is one of the beauties of trademark law – it is dynamic. What is a trademark today can be generic tomorrow. Believe it or not, but ZIPPER once used to be a trademark in association with rubber boots. The word has a different, broader meaning now.

Failure to Function as a Trademark

An offshoot of a generic mark is a popular term that resonates generally within the culture, but fails to identify a particular source of goods and services. One reason that these types of marks are not trademarks because they “fail to function” as such.

There are a multitude of recent examples of this, with OK BOOMER being the latest trend.[6]

Another recent example is Ohio State’s attempt to register THE as a trademark. Remember that one? The USPTO has initially refused to register this proposed mark on grounds that it “fails to function” as a trademark. This was the exact reason for the initial refusal of “THE” by the USPTO: “Registration is refused because the applied-for mark as used on the specimen of record is merely a decorative or ornamental feature of applicant’s clothing and, thus, does not function as a trademark to indicate the source of applicant’s clothing and to identify and distinguish applicant’s clothing from others.” Ohio State will still have the opportunity to respond and demonstrate how THE is associated with clothing in the minds of the consuming public, but it is a heavy burden given the lack of inherent distinctiveness in the mark itself.

A similar thing happened with LeBron’s TACO TUESDAY application. The USPTO issued an initial refusal to register on grounds that “Taco Tuesday” is a “commonplace message” and “does not function as a trademark or service mark to indicate the source of applicant’s goods and/or services and to identify and distinguish them from others.” The examining attorney on that file further stated that “[t]erms and expressions that merely convey an informational message are not registrable” and that “[d]etermining whether the term or expression functions as a trademark or service mark depends on how it would be perceived by the relevant public.”[7]

Trademark law is clear on this issue. A commonplace term, message, or expression widely used by a variety of sources that merely conveys an ordinary, familiar, well-recognized concept or sentiment cannot be a trademark because it fails to function as a trademark. There must be some extra layer of distinctiveness that demonstrates the proposed mark functions as a source identifier. Without that next step, there is no trademark.

Applications keep pouring in nonetheless. As mentioned, there are now seven OK BOOMER variants in the pipeline. There are also seven pending applications for variants of TACO TUESDAY filed since 2018 (not just LeBron’s application). There have been 26 different applications for ALTERNATIVE FACTS since 2017. One actually managed to register as a trademark – for beer. That is actually rather creative. There are many other examples. COVFEFE? 41 applications! None have registered to date and all but three have been abandoned or denied in full.

This is lighting money on fire, though the USPTO is happy to take your application fees.

One of the OK BOOMER applications is for “entertainment services” in the form of a television show. Filed by Fox Media LLC, naturally. In theory, this could actually mature into a proper trademark use in that the phrase has been repurposed for television. Of course, by the time this hypothetical show title actually reaches the airwaves, the “ok, boomer” craze will almost certainly have worn itself out and the name would be more cringe-worthy than topical. That is the flip side of trademarks – some have an extremely short shelf-life of commercial value.

—

(For a more detailed and sourced analysis of the “Failure to

Function” issue, please

read the recent law review article by Alexandra J. Roberts in the Iowa Law

Review journal.)

[1] http://tmsearch.uspto.gov/bin/showfield?f=toc&state=4801%3Auap1hi.1.1&p_search=searchss&p_L=50&BackReference=&p_plural=yes&p_s_PARA1=&p_tagrepl%7E%3A=PARA1%24LD&expr=PARA1+AND+PARA2&p_s_PARA2=ok+boomer&p_tagrepl%7E%3A=PARA2%24COMB&p_op_ALL=AND&a_default=search&a_search=Submit+Query&a_search=Submit+Query

[2] See also Trade-Mark Cases, 100 U.S. 82, 97 (1879).

[3] See generally Alexandra J. Roberts, Trademark Failure to Function, 104 Iowa L. Rev. 1977, fn 11 (2019).

[4] I was interviewed for that article, so of course I am linking it here.

[5] See TMEP § 1209.01(c); In re Dial-A-Mattress Operating Corp., 240 F.3d 1341, 57 USPQ2d 1807, 1811 (Fed. Cir. 2001); In re Am. Fertility Soc’y, 188 F.3d 1341, 1346, 51 USPQ2d 1832, 1836 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

[6] The most common example is a random word derived from something Donald Trump says or tweets.

[7] See also In re Eagle Crest, Inc., 96 USPQ2d 1227, 1229 (TTAB 2010).

0 Comments

1 Pingback