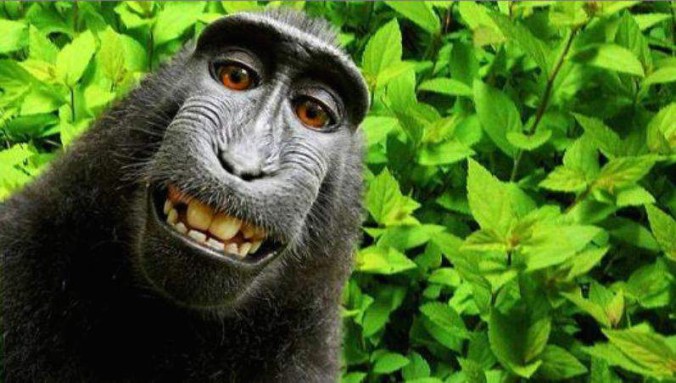

Copyright is the exclusive domain of humans. So says the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. Oh, and the U.S. Copyright Office, too. A recent appeal made on behalf of haplorhine primates everywhere has failed to extend the law to allow monkeys to be the authors or owners of copyrights in the United States. How and why are we even talking about this? Because in 2011, a monkey in Indonesia took a selfie. The monkey even smiled for the camera!

The resulting images created a firestorm for copyright law when the owner of the camera began publishing the monkey’s pictures and asserting copyright claims against others. On September 22, 2015, PETA filed suit on grounds that the camera owner and his publishing company were infringing the monkey’s copyrights. As if that lawsuit was not bizarre enough, it did set the stage for one of the more amusing Motions to Dismiss ever filed in federal court. Nevertheless on January 7, 2016, Judge Orrick granted the Motion to Dismiss and held that a monkey cannot be the owner or author of a copyright.

While the monkey, now known as “Naruto,” may not be able to enforce any copyrights, it does raise interesting legal issues to address and consider.

Copyright Authorship

The word “author” is not precisely defined by the U.S. Copyright Act. Under U.S. Copyright law, copyrights are initially owned by the “author” or a work that is fixed in a tangible medium of expression.[1] But who or what is the author of a work? First, an author must be a human being.[2] The resulting work, meanwhile, must be original and be independently created by the author.[3] The “author” must therefore be the person that actually created the underlying work. Authorship does not extend to anyone who did not directly contribute to the work. Works that are not created by a human are not protected by U.S. copyright law.[4]

This is where the “monkey selfie” becomes a legal quagmire. Photographs are normally the domain of copyright law. Yet the product of a non-human cannot be copyrighted. David Slater, the British photographer seeking to claim authorship and ownership, admittedly did not “take” the actual photo of the monkey in question. He states that he left the camera unattended but that “[i]t took three days of blood, sweat and tears to get the selfie in which I had to be accepted by the group of monkeys before they would allow me to come close enough to introduce them to my camera equipment.” Unfortunately for Mr. Slater, the “blood, sweat and tears” assertion has long since been debunked as a basis for claiming copyright. There is no “sweat of the brow” factor in copyrightability here.[5] While Mr. Slater may be the owner of copyrights in Britain, it does not necessarily protect him under U.S. law.

Accordingly, the monkey took the photo. The monkey is the “author” for all intents and purposes as we understand that term of art. But the monkey cannot own copyrights. Likewise, photographs that are taken by non-humans cannot be copyrighted under U.S. law. Therefore, there are no copyrights to be infringed. Theoretically the photos should be public domain.

Standing to Sue

Even if copyright law allowed a monkey to own the photo as property, it would be hard for the monkey to enforce his hypothetical rights. PETA brought the lawsuit “on behalf of” Naruto. But PETA lacked what is called “standing to sue” as PETA is not the owner or the assignee of any copyrights or other legal interests. “Standing” is the capacity of a party to bring suit in court. Under the Constitution, a party must have a direct interest or stake in the outcome of any legal dispute to have proper standing. Having a general, non-specific interest is not sufficient. Without an assignment of rights in the photo or a transfer of sufficient interests to grant it the right to sue on Naruto’s behalf, PETA would lack standing to sue under U.S. law. Additionally, as a non-human, Naruto also lacks capacity to transfer or assign any purported ownership rights to PETA.[6] Transfer of copyright ownership must be in writing.[7] PETA therefore had no tangible basis to make legal claims on Naruto’s behalf.

Essentially, the law protects Naruto from having a third-party falsely claim to be his agent or representative. Even if we assume Naruto could be the “owner” or the photo, the law protects him from having PETA (or anyone else) from being able to claim that Naruto has assigned them interest in the underlying copyrights or the right to sue for monetary damages on his behalf.

Yes, PETA actually sued for the recovery of monetary damages arising from Mr. Slater’s allegedly infringing uses of the alleged copyrighted work. Granted, PETA claimed any monetary proceeds from the litigation would be “used to assist Naruto” and his habitat but the Court correctly deemed this to be an invalid basis to claim legal rights and/or the standing to sue on Naruto’s behalf in federal court.

The question now is whether this image is fully in the public domain or whether Mr. Slater can claim derivative ownership and seek to enforce any rights within the United States. Mr. Slater has stated his intent to enforce copyrights elsewhere, using his British copyright registrations, but he may be precluded from extending any rights into the United States. After all, if Naruto cannot assign his rights in ownership to PETA, he cannot assign them to Mr. Slater either.

In the end, I guess I am just jealous that a monkey takes a better photo than I do.

[1] 17 U.S.C. §§ 102(a), 201(a).

[2] Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 58 (1884).

[3] 17 U.S.C. § 102(a).

[4] See Compendium of the U.S. Copyright Office Practices § 313.2.

[5] See Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991).

[6] 17 U.S.C. § 201(d)

[7] 17 U.S.C. § 204(a).

Recent Comments