June 5, 2017

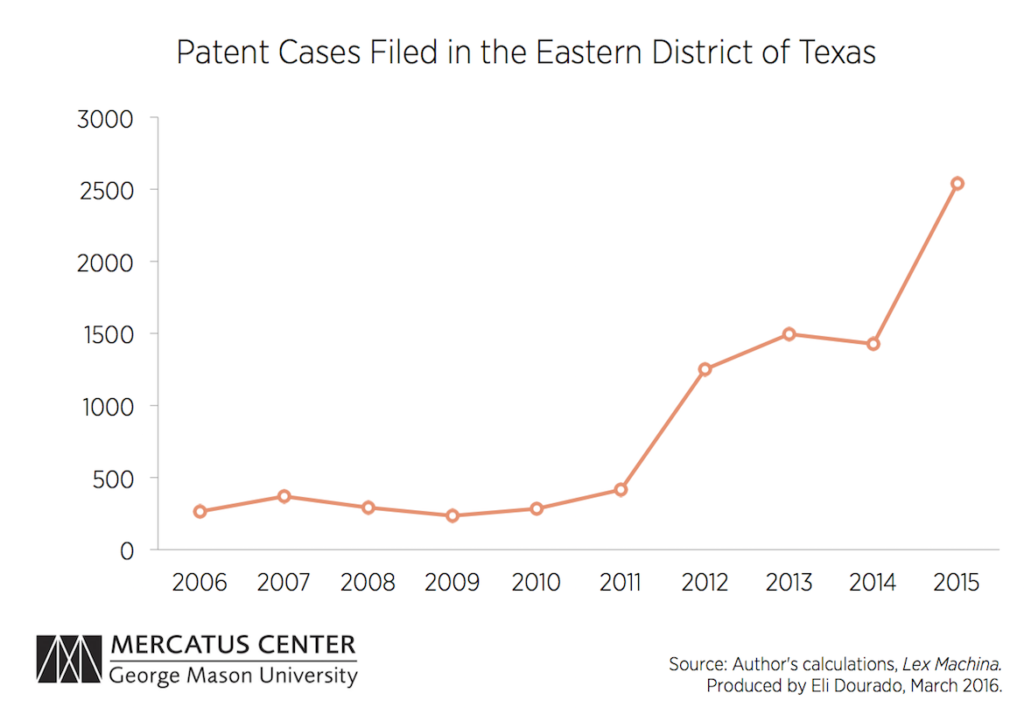

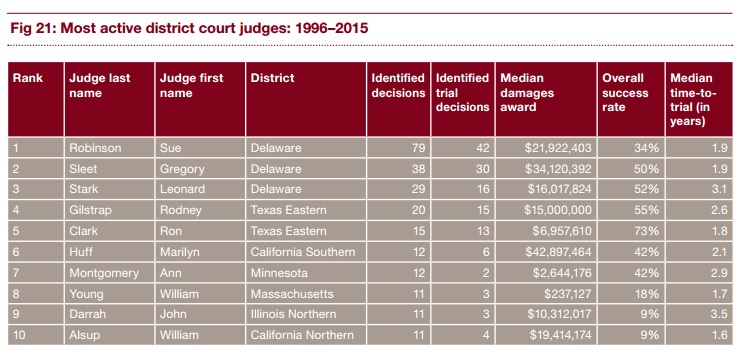

Marshall, Texas is a town of less than 25,000 residents in East Texas.[1] It is closer to Shreveport, Louisiana than it is to Dallas or to Houston. Nevertheless, since the late 1990s, Marshall has become the epicenter for a series of high-profile patent litigation cases. In 2015, there were nearly 6,000 patent infringement cases filed in the United States. At least 1,500 of these filings ended up before Judge Rodney Gilstrap,[2] a judge for the Eastern District of Texas, in the Marshall, Texas division. This was no accident.

As of last month, however, this may all be subject to change.

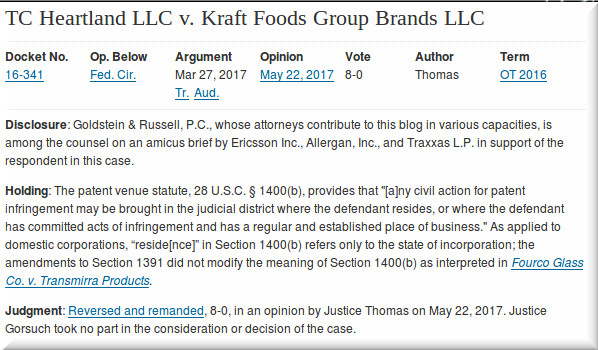

On May 22, 2017, in TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC, the United States Supreme Court addressed a dispute regarding the patent venue statute and unanimously held that civil actions for patent infringement may only be brought in the judicial district where the defendant resides or where the defendant has committed acts of infringement and has a regular and established place of business. Prior to TC Heartland, patent owners could choose to file suit in most any state given that most corporations made or sold products nationwide. This allowed certain courts to set up shop as patent “rocket dockets” which encouraged litigators to choose their venue.

This is how one judge in Marshall, Texas came to oversee, on average, nearly a quarter of all patent infringement cases filed in the United States. Now that TC Heartland is the rule of the land, there are three primary issues to address and explore: (1) how did Marshall, Texas become a “rocket docket” for patent cases?; (2) what rule did the Supreme Court actually change?; and (3) what is likely to happen now?

Patent Litigation and the Rise of “Rocket Dockets”

The wheels of justice move slowly. Patent infringement actions are no different. The act of merely acquiring a patent after filing an application with the United States Patent and Trademark Office typically takes in excess of 25 months[3] – over two years! Considering that the term of a patent is 20 years from the date of filing,[4] 10% of the life of a patent may be lost just waiting for the USPTO to grant you the actual certificate. Then, after a patent holder discovers that there is a likely infringer of this patented invention, research has indicated that the average time from the filing of a lawsuit to the actual trial date is 2.5 years.[5]

We also know that time is money, and the typical cost for trying to stop an infringer in court nearly always exceeds $1,000,000. If your infringement contentions seek damages in excess of $25 million, your legal fees are likely to be in the $5 million range if it goes to trial.[6] That is independent of a presumed verdict in your favor, too. This incentivizes litigants to seek out shortcuts or expedited pathways to a verdict. If only there were a court that understood these sensitive factors and could make itself available to these desirous litigants in need… and voila! The recipe for a “rocket docket” is set.

The basis for any good rocket docket analysis is the understanding of the “venue” statutes. Procedurally speaking, venue is where the law allows a plaintiff to file suit against a defendant. The law provides certain parameters to both plaintiffs and defendants in an attempt to ensure that venue is beneficial or convenient to all parties if a case goes to trial.[7] The law recognizes that it would be unfair to make an individual residing in New York to travel to Texas for a dispute that occurred entirely in New York. Unless there are other factors that would make Texas a state of interest to the case. Of course, venue should not be confused with “jurisdiction” – which separately requires a court to have the authority to hear or oversee particular types of cases in an approved setting. A bankruptcy court cannot typically hear a divorce case, for example. In a more topical example, for patent and copyright cases – these rights are the exclusive jurisdiction of federal law.[8] This means that a state court lacks jurisdiction to hear a patent or copyright infringement case.

Typically, in most civil cases, venue is where the defendant resides, the judicial district where a substantial part of the events at issue occurred, or where a piece of real property at issue is situated.[9] Patent law has historically been considered an ugly duckling, however, and it has its own venue statute. Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1400(b):

(b) Any civil action for patent infringement may be brought in the judicial district where the defendant resides, or where the defendant has committed acts of infringement and has a regular and established place of business.

This has been the framework for patent venue since 1948.[10] Over time, creative litigants and their attorneys have worked to engage in what is known as “venue shopping” to find courts that meet the parameters for venue. With the actual language of the patent venue statute being broad, this left a lot of room for maneuverability. Especially considering that most patent defendants were typically large companies or manufacturers and distributors which resided and/or “has a regular and established place of business” in every state in the country.

While a particular origin point cannot be determined with specificity, the Eastern District of Texas steadily gained a reputation for being friendly to patent plaintiffs and unfriendly to defendants.[11] By the late 1990s, Marshall, Texas became a veritable cottage industry for technology companies, patent owners, and their local counsel. Many of these companies established physical offices of locations right next to the courthouse in Marshall or in nearby Tyler, Texas.[12] This reputation for being patent-friendly was subtly encouraged by the Eastern District, too. Whether intentionally or not, patent defendants found it difficult to win cases at summary judgment (before trial) and judges may even be prone to let highly-technical issues be heard and decided by non-technical juries.[13] These juries also became prone to awarding big-dollar damages verdicts in favor of plaintiffs,[14] who are now able to make emotional pleas to these juries that they are “local” and that their businesses serve local interests in Texas.

[image by PwC 2016 patent litigation study]

By the end of 1999, Marshall was a growing patent litigation rocket docket, but it was during the early 2000s that it became the preferred location. By 2008, more patent cases were filed in the Eastern District of Texas than any other court in the country.[15] Patent infringement cases were now big business for this small town in East Texas. Furthering its reputation as being plaintiff-friendly, while the recent trend is that most patent cases have been resolved in favor of the defendant, the success rate for plaintiffs in Marshall was over 54% from 1996-2015, with a median damages award of $15,000,000.[16] It is therefore no surprise that patent owners and their lawyers are eager to seek out the friendly confines of Marshall, Texas to hear their claims of infringement.

And then the United States Supreme Court stepped in.

Patent Venue and the Supreme Court

In 1957, in the Fourco Glass case, the Supreme Court re-affirmed that a corporate entity’s place of residence with regard to venue in patent cases was to be determined more narrowly than in other civil disputes.[17] The Supreme Court recognized that the general venue statute of § 1391(c) was amended to be broader, but that was not intended to have any bearing on the patent venue statute set forth by § 1400(b). The Fourco Glass case was the law of the land on paper for 60 years, but in practice this rule slowly eroded over the years and courts routinely broadened what it meant for a corporate entity to “reside” in a state.

This culminated in a decision by the Federal Circuit in 2016 which held that the definition of “reside” as set forth by the general civil venue statute of § 1391(c) also applied to the definition of “reside” in the patent venue statute of § 1400(b). This is the TC Heartland case.

The Supreme Court unanimously slapped down the Federal Circuit’s interpretation of § 1400(b).[18]

[image from SCOTUSblog]

The origin of the TC Heartland dispute can be traced back to 1988, when the general venue statute was amended to use the term “resides” instead of “inhabit[s]” as applied to corporate entities.[19] This amendment also stated that the new terminology in § 1391 applied to all venue provisions “under this Chapter” – which may or may not have been intended to include § 1400(b). In VE Holding Corp. v. Johnson Gas Appliance Co., 917 F. 2d 1574, 1578 (Fed. Cir. 1990), the Federal Circuit sided with the broader interpretation of “resides” for all cases, including patent cases.

This VE Holding decision remained essentially unchallenged for 25 years. It was the impetus for the Marshall, Texas rocket docket.

Now, while it may be hard to fathom that billions of dollars may have been invested by litigants and patent holders based on the scope of the word “resides” – this is effectively what brought about the TC Heartland case. Ironically, TC Heartland did not originate in the Eastern District of Texas. The TC Heartland plaintiff is an entity that manufactures flavored drink mixes. The corporation is registered under Delaware law, but with a principal place of business in Illinois. The defendant is a competitor entity that is registered under Indiana law and also with a principal place of business in Indiana. The plaintiff nevertheless sued the Indiana company in the federal district court of Delaware, on the flimsy grounds that the defendant shipped allegedly infringing products into Delaware.

It is undisputed that the defendant was not registered in Delaware nor did it have a principal place of business in Delaware. But when the defendant moved to transfer venue to Indiana, based on the 1957 precedent of Fourco Glass, the Delaware court denied these arguments. Instead, the Delaware court relied on the 1990 VE Holding case which held that definition of “reside[s]” is broader and allows for venue when the defendant merely shipped a product to that state. The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision to deny the motion to transfer based on this same VE Holding precedent.

The Supreme Court fundamentally disagreed with this application. Instead, the Supreme Court held that the patent venue statute was specifically enacted as a standalone statute apart from the general venue statute of § 1391 and that the Federal Circuit’s interpretation which effectively merged the two laws was in error. With TC Heartland, the Supreme Court emphatically restated that “residence” for a corporate entity under § 1400(b) refers only to the State of incorporation, and that Congress did not change this definition when it amended the separate venue statute in § 1391. Thus, the 1957 patent venue interpretation is once again the law of the land.

Of course, the analysis of legislative history and Congressional intent is decidedly unsexy to the layperson. But the fallout from TC Heartland may have substantial practical implications. Not just to lawyers and patent owners but also to these “rocket docket” courts that have paved the way for the growth of related business interests in towns such as Marshall, Texas.

After TC Heartland – What Happens Now?

What happens to cases that are already filed and pending in the Eastern District of Texas? The answer is “we do not know yet.” Defendants may seek to dismiss cases for improper venue based on TC Heartland. These same defendants may also pursue renewed motions to transfer venue to their State of incorporation. Though there will be questions of judicial efficiency and the burdens of re-litigating issues in other courts. Many defendants may decide that they are already far enough along the path of litigation and that they might as well just see it through to the end, even if Marshall, Texas is generally favorable to plaintiffs.

Every litigant will need to engage in its own venue-specific cost-benefit analysis.

Meanwhile, for future patent cases, there is a new calculus. Or rather, an old calculus that is once again back in fashion. Texas is a big state with a lot of corporate interests, but it is unlikely that Judge Gilstrap will be seeing 25% of all patent cases filed going forward. Marshall, Texas is likely to see a massive reduction in its patent docket overall. On the flip side, there has long been a trend for corporate entities to register in the State of Delaware. Corporate laws are seen as friendly in Delaware. The TC Heartland decision will only encourage more patent disputes to find their way Delaware courts. Likely at the expense of East Texas.

Not that Marshall, Texas will suddenly become a technology ghost town. There are still many technology companies in the area. Tyler, Texas is seen as a growing corridor for many small technology business corporate interests.[20] Creepy Toadies songs notwithstanding. Many of the patent owners and technology incubators already set up shop in Marshall and Tyler due in part to the patent rocket docket. The infrastructure is already there for these corporate entities to remain. For the time being. Presumably, many of them are registered as Texas corporate entities. Any of their disputes can still be resolved in the plaintiff-friendly court nearby.

Of course, there are many lawyers that created an entire business model on being “local counsel” for out-of-state law firms that sought to litigate patent cases in Texas. This may be the sector of the local economy that is hardest hit by the Supreme Court’s decision. These lawyers may be scrambling to join law firms. Or they may be forced to expand the scope of their practice and the services they offer. Such is the nature of patent litigation and technology. It constantly evolves and we have to adjust to the changing landscapes.

Moral of the story? Words matter. Entire local economies can rely on the meaning and legal application of one simple, seemingly innocuous word.

________________

[1] https://suburbanstats.org/population/texas/how-many-people-live-in-marshall

[2] https://lexmachina.com/14318/

[3] https://www.uspto.gov/dashboards/patents/main.dashxml

[4] 35 U.S.C. § 154(a)(2).

[5] http://www.pwc.com/us/en/forensic-services/publications/assets/2016-pwc-patent-litigation-study.pdf

[6] https://www.cnet.com/news/how-much-is-that-patent-lawsuit-going-to-cost-you/

[7] http://dictionary.law.com/Default.aspx?selected=2216

[8] Patent and copyright laws are derived from the U.S. Constitution and federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction.

[9] 28 U.S.C. § 1391 et seq.

[10] https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/28/1400

[11] As a matter of full disclosure, I am a licensed patent attorney in the State of Texas. I have appeared as counsel of record for a handful of cases that were filed in the Eastern District of Texas. None of these cases remain pending.

[12] https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2013/01/east-texas-courts-are-back-on-top-for-patent-lawsuits/

[13] Id.

[14] http://www.thejuryexpert.com/2010/03/east-texas-jurors-and-patent-litigation/

[15] Id. (citing http://www.ropesgray.com/files/upload/Article_Freedom_9-17-09.pdf)

[16] http://www.pwc.com/us/en/forensic-services/publications/assets/2016-pwc-patent-litigation-study.pdf (see also chart in image above)

[17] See Fourco Glass v. Transmirra Prods., 353 U.S. 222 (1957).

[18] https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/16pdf/16-341_8n59.pdf

[19] 28 U.S.C. § 1391 (as amended).

Recent Comments